|

| Holding a French horn |

Holding the Instrument

When playing the horn,

place the edge of the bell on your right knee and bring the horn to your lips.

Never lean forward to play it, and don't pick it up and hold it so the

bell is pointing directly to the right.

Using the Right Hand

The right hand is always

placed inside the bell; this is a characteristic of the French horn that has

remained throughout history. Usually younger students are told not to

worry about their right hand since they have smaller hands, but more experience

players who would like to play with good intonation will have to learn. The

hand should go comfortably inside the bell, curved with the inside and not

blocking it. The sound is muffled if you block the bell.

Single vs. Double Horn

A single horn can only play in F, whereas a double horn has extra tubing

that allows it to play in both F and Bb.

(A thumb trigger switches between the two sides.) This extra tubing makes it heavier and much

more expensive. Students usually start

on a single horn because their repertoire isn't advanced enough to require the

extra notes. However,

all experience horn players will need to be able to switch between F and Bb. The music store I go to doesn't rent double horns for this reason; they only sell them.

Cleaning out the Instrument

Mrs. Harvison showed me how to get the spit out of a French horn. It requires emptying four different tuning valves since there isn't a spit valve (unlike other brass instruments.) Take out the tuning slide one by one and shake them. There’s a special wrist maneuver to perform with one that’s particularly curvy. It's important to keep the valves pressed down while inserting and removing the slides in order to help with the pressure. I've also seen a French horn player I know spin his French horn while he's holding it to distribute the spit. This must make it easier to clean out later.

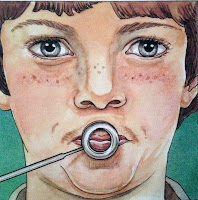

Embouchure

French horn requires a lot of stability in the lower lip and a small embouchure, so clarinet players are often good horn players. Clarinet has a firm embouchure, especially in the bottom lip, and a strong foundation is essential with French horn. (This was probably why French horn is easier for me to play than trumpet.)

|

| French horn embouchure |

Since the French horn

embouchure is so small, it also tires easily at first. If you find yourself unable to get notes out,

no matter how hard you try, you should put the horn down for a few minutes and

go do something else. It happens

sometimes. Then, once you've rested for

a bit, go back to playing.

As you play higher, the

hole that you’re blowing air through gets smaller and your lips get tighter. The lips are looser for low notes. Mrs. Harvison suggested directing your air

upwards and focusing on a point above you to help get the higher notes out. Singing the note or hearing it in your head

before you play it also helps. (Yes, I

just admitted that singing can actually help!)

Finally, becoming familiar

with the embouchure is very important to playing music correctly. Since the partials are so close together,

it’s easy to start on the wrong note. One

of the first things to teach kids on French horn is to instantly start over if

you don’t get the correct starting note. If you don't start on the right note, the whole song could be thrown

off. Teaching students to reset their

embouchure if they don't start correctly teaches them to listen to the other

parts in the band and helps them develop and become familiar with their

embouchure.